On 11th November 1920 simultaneous acts of interment took place at Westminster Abbey in London and at the Arc de Triomphe in Paris. At each location the remains of an unknown soldier who had died in the Great War were laid to rest, a representative and symbol for all those whose loved ones had no known grave. The burials of these British and French soldiers are the first examples of a Tomb Of The Unknown Soldier.

It was in 1916 that army chaplain Reverend David Railton saw a rough wooden cross marking a grave in a back garden at Armentières, on the Western Front, in pencil on the cross were the words ’An Unknown British Soldier’. In 1920 Railton suggested to the Dean of Westminster that an unidentified British soldier should be buried ‘amongst the kings’ in Westminster Abbey to represent the hundreds of thousands of men from throughout the Empire who had died during the conflict. The Dean readily agreed and the idea was supported by David Lloyd George, the Prime Minister.

The remains of four unknown soldiers were exhumed from four of the battlefields, (the Aisne, the Somme, Arras, and Ypres), to be taken to a chapel near Arras where they were laid on stretchers covered by Union Flags. Brigadier General Wyatt, responsible for selecting the Unknown Warrior, did not know which battlefields they had come from and chose one of the bodies at random. The three remaining were taken away to be reburied whilst a service led by chaplains for the Church of England, Roman Catholic Church, and Non-Conformist churches was said for the fourth body which was placed in a plain coffin.

The next day (8th November 1920) the chosen soldier was taken to Boulogne where the French 8th Infantry Regiment kept an overnight vigil before the coffin was prepared for its return to England. The plain coffin was placed in a casket made from oak timbers from Hampton Court Palace; King George V had personally chosen a crusader sword from the royal collection to be fixed to the top of the casket along with an iron shield on which was engraved the words ‘A British Warrior who fell in the Great War 1914–1918 for King and Country’. The casket was covered with the flag that Rev. Railton had used as an altar cloth during the War (known as the Ypres or Padre’s Flag, which now hangs in St George’s Chapel).

Six black horses then drew the coffin on an open waggon through the city of Boulogne and down to the harbour. The mile-long procession, escorted by a division of French troops, was led by 1,000 local schoolchildren who marched solemnly as all the church bells tolled and trumpets sounded Aux Champs (the French equivelant of The Last Post). Marshal Foch saluted the coffin as it was carried aboard HMS Verdun which was escorted across the English Channel by six battleships. Its arrival in Dover on 10th November was marked by a 19-gun salute, an honour normally reserved for a Field Marshall.

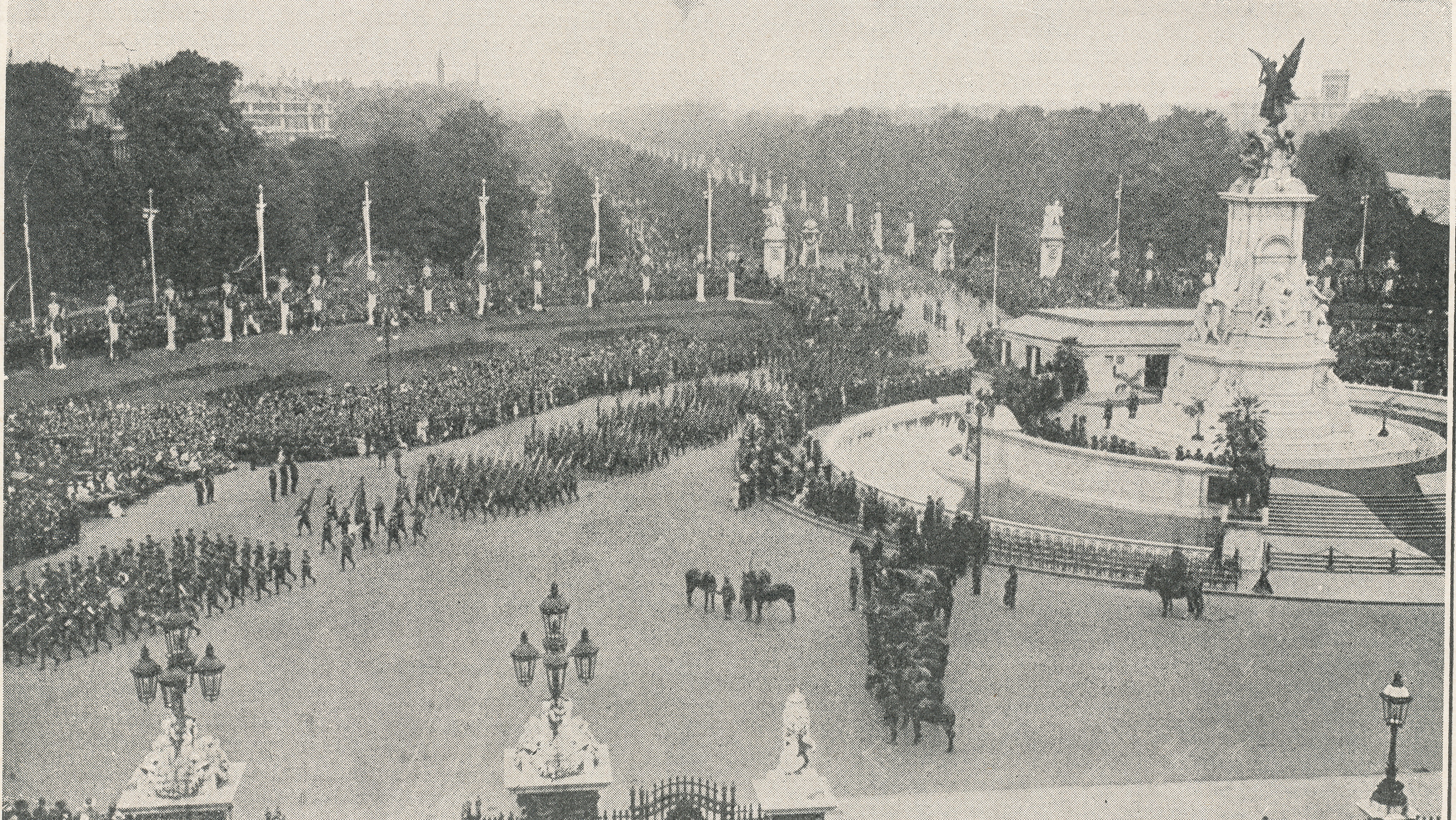

From Dover the Unknown Warrior was taken by train to Victoria Station in London where he remained overnight before the casket was placed on a gun carriage drawn by black horses of the Royal Horse Artillery in the early morning of 11th November. Huge silent crowds lined the routed as the cortege made its way to Whitehall, the only sound another Field Marshal’s salute from guns in Hyde Park. A temporary Cenotaph had been the focus of commemorations the previous year, on 11th November 1919, and this had now been replaces with a permanent structure. The gun carriage carrying the Unknown Warrior halted at this new permanent memorial which was unveiled by King George V who placed a wreath of red roses and bay leaves on the coffin, the accompanying card read ‘In proud memory of those Warriors who died unknown in the Great War. Unknown, and yet well-known; as dying, and behold they live. George R.I. November 11th 1920’. After laying his wreath the king then followed the casket on its final journey to Westminster Abbey, accompanied by other members of the Royal Family and minister of the government.

When the Unknown Warrior arrived at the Abbey 100 recipients of the Victoria Cross provided a Guard of Honour as he was carried to the West Nave. During the burial service the King dropped a handful of French soil onto the coffin as it was lowered into the grave and Reveille was sounded by trumpeters (the Last Post had already been sounded at the Cenotaph). The Padre’s Flag was laid over the grave. Guests of honour at the ceremony included royalty and statesmen, and more than a hundred women who had lost their husband and all of their sons during the four terrible years of conflict which had taken such a toll on Europe. They watched as the coffin was interred with soil from the major battlefields, and a guard of honour formed to flank the tomb as tens of thousands of mourners filed past in silence; for many this was the only place they would ever be able to visit as their own loved ones had ‘no known grave’ somewhere in northern Europe.

For the remainder of the day servicemen kept watch at each corner of the grave while thousands of mourners filed past. When night fell and the Abbey was closed the guard continued to stand, arms reversed, in the light of four flickering candles to keep watch through the night.

Special permission had been given to make a recording of the service but very little of it was of good enough quality to be included on a record which became the first electrical recording ever to be sold to the public.

On 18th November the grave was filled with 100 sandbags of earth from the battlefields; a temporary stone was placed over it with the inscription

‘A BRITISH WARRIOR WHO FELL IN THE GREAT WAR 1914-1918 FOR KING AND COUNTRY. GREATER LOVE HATH NO MAN THAN THIS.’

The Tomb Of The Unknown Warrior became a focus for the grieving of a nation, and also an aid to healing for all those who had no known grave for their loved one – who was to say that he did not lie here in Westminster Abbey? On 17th October 1921 the Unknown Warrior was awarded the United State’s highest award for valour, the Medal of Honour, by General Pershing; the medal still hangs on a pillar close to the tomb.

The Tomb is now covered with a black marble stone which was unveiled during a special service on 11th November 1921 at the same time that the Padre’s Flag was dedicated, this, too, is still on display in Westminster Abbey.

When Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon married the future King George VI in 1923 she laid her bouquet at the Tomb in memory of her brother Fergus, who died in 1915 during the Battle of Loos and is listed amongst the missing on the memorial there. Ever since that day the bouquets of all Royal brides who have married in Westminster Abbey have been laid on the Tomb. Before she died the former Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon, then Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother, asked for her wreath to be laid on the Tomb Of The Unknown Warrior, this act of remembrance was carried out by Queen Elizabeth II on the day after her mother’s funeral.

The name of the serviceman intered in the Tomb is truly unknown, he could be a member of any of the three services – Army, Navy, or Air Force – and could have been from the British Isles or one of the Dominions or Colonies which, at that time made up the British Empire. As such he represents all those who died and have no known grave or memorial. In memory of the sacrifice made by so many the heads of state from over 70 countries have laid wreaths in memory of the Unknown Warrior buried in Westminster Abbey.

The Tomb Of The Unknown Warrior is the only tombstone in Westminster Abbey which people are forbidden to walk on. The words engraved on it say

Beneath this stone rests the body

Of a British warrior

Unknown by name or rank

Brought from France to lie among

The most illustrious of the land

And buried here on Armistice Day

11 Nov: 1920, in the presence of

His Majesty King George V

His Ministers of State

The Chiefs of his forces

And a vast concourse of the nation

Thus are commemorated the many

Multitudes who during the Great

War of 1914 – 1918 gave the most that

Man can give life itself

For God

For King and country

For loved ones home and empire

For the sacred cause of justice and

The freedom of the world

They buried him among the kings because he

Had done good toward God and toward

His house

Around the main inscription are four New Testament quotations:

The Lord knoweth them that are his (2 Timothy 2:19)

Unknown and yet well known, dying and behold we live (2 Corinthians 6:9)

Greater love hath no man than this (John 15:13)

In Christ shall all be made alive (1 Corinthians 15:22)

The artist Frank O. Salisbury attended the burial and made a sketch of the event which was attended by leading politicians, senior military figures and members of the Royal Family led by King George V. The painting which he developed from the sketch hangs in Committee Room 10 in the Houses of Parliament.

Most people are familiar with the Cenotaph in London’s Whitehall which is the focus of Britain’s National Service of Remembrance every November and commemorates British and Commonwealth servicemen and women who died in the two World Wars and later conflicts. The ceremony is televised and is attended by Prince Charles (representing the Queen), religious leaders, politicians, representatives of state and the armed and auxiliary forces, all of whom gather to pay their respects to those who gave their lives defending others. It is a well-known and well-loved ceremony, yet many people are unaware of the history of the Cenotaph and how it came to be where it is.

Most people are familiar with the Cenotaph in London’s Whitehall which is the focus of Britain’s National Service of Remembrance every November and commemorates British and Commonwealth servicemen and women who died in the two World Wars and later conflicts. The ceremony is televised and is attended by Prince Charles (representing the Queen), religious leaders, politicians, representatives of state and the armed and auxiliary forces, all of whom gather to pay their respects to those who gave their lives defending others. It is a well-known and well-loved ceremony, yet many people are unaware of the history of the Cenotaph and how it came to be where it is.

epic historical novel about Lawrence of Arabia, one of the most compelling characters in British history.

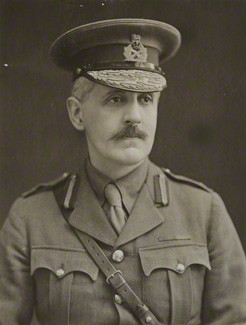

epic historical novel about Lawrence of Arabia, one of the most compelling characters in British history.  As we commemorate the ending of the First World War it is fitting that we remember all those who paid the ultimate price. We are all aware of cemeteries around the world which contain the graves of soldiers who died far from home, and if you have ever visited one you will have been impressed by the standard of care which is taken to keep these places of remembrance at their best. This work is carried out by The Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) which was the brainchild of Sir Fabian Ware. The CWGC builds and maintains cemeteries and memorials in more than 150 countries and territories and also creates and preserves archives with extensive records of the fallen. Ware was 45 when war broke out and so too old to fight but he was determined to play his part so became the commander of a mobile unit in the British Red Cross. Arriving in France in 1914 he was appalled and saddened at the huge loss of life he saw, and also by the fact that there was no official way of documenting and recording the graves. Determined that none of the fallen would be forgotten he organised for his unit to begin recording and caring for all the graves they could find. Municipal cemeteries were soon full and Ware negotiated for France to grant land in perpetuity to Britain which would become responsible for the management and maintenance of the graves there. People heard about Ware’s work and he began to get letters from people asking for photographs of the graves of their loved ones. By 1917 17,000 photos had been sent. At the same time graves were being recorded in Egypt, Greece and Mesopotamia as well as France.

As we commemorate the ending of the First World War it is fitting that we remember all those who paid the ultimate price. We are all aware of cemeteries around the world which contain the graves of soldiers who died far from home, and if you have ever visited one you will have been impressed by the standard of care which is taken to keep these places of remembrance at their best. This work is carried out by The Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) which was the brainchild of Sir Fabian Ware. The CWGC builds and maintains cemeteries and memorials in more than 150 countries and territories and also creates and preserves archives with extensive records of the fallen. Ware was 45 when war broke out and so too old to fight but he was determined to play his part so became the commander of a mobile unit in the British Red Cross. Arriving in France in 1914 he was appalled and saddened at the huge loss of life he saw, and also by the fact that there was no official way of documenting and recording the graves. Determined that none of the fallen would be forgotten he organised for his unit to begin recording and caring for all the graves they could find. Municipal cemeteries were soon full and Ware negotiated for France to grant land in perpetuity to Britain which would become responsible for the management and maintenance of the graves there. People heard about Ware’s work and he began to get letters from people asking for photographs of the graves of their loved ones. By 1917 17,000 photos had been sent. At the same time graves were being recorded in Egypt, Greece and Mesopotamia as well as France.

It is late summer in East Sussex, 1914. Amidst the season’s splendour, fiercely independent Beatrice Nash arrives in the coastal town of Rye to fill a teaching position at the local grammar school. There she is taken under the wing of formidable matriarch Agatha Kent, who, along with her charming nephews, tries her best to welcome Beatrice to a place that remains stubbornly resistant to the idea of female teachers. But just as Beatrice comes alive to the beauty of the Sussex landscape, and the colourful characters that populate Rye, the perfect summer is about to end. For the unimaginable is coming – and soon the limits of progress, and the old ways, will be tested as this small town goes to war.

It is late summer in East Sussex, 1914. Amidst the season’s splendour, fiercely independent Beatrice Nash arrives in the coastal town of Rye to fill a teaching position at the local grammar school. There she is taken under the wing of formidable matriarch Agatha Kent, who, along with her charming nephews, tries her best to welcome Beatrice to a place that remains stubbornly resistant to the idea of female teachers. But just as Beatrice comes alive to the beauty of the Sussex landscape, and the colourful characters that populate Rye, the perfect summer is about to end. For the unimaginable is coming – and soon the limits of progress, and the old ways, will be tested as this small town goes to war.

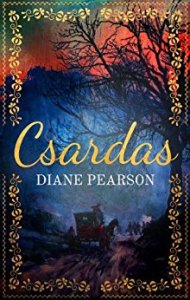

CSARDAS – taken from the name of the Hungarian national dance – follows the fortunes of the enchanting Ferenc sisters from their glittering beginnings in aristocratic Hungary, through the traumas of two World Wars.

CSARDAS – taken from the name of the Hungarian national dance – follows the fortunes of the enchanting Ferenc sisters from their glittering beginnings in aristocratic Hungary, through the traumas of two World Wars.