There is no symbol in history which has such diametrically opposed meanings as the swastika. Many people know it only as a symbol of Nazi Germany, but its origins lie much further back in history – it has been used for millennia, and is older even than the well known ancient Egyptian symbol of the ankh. The symbol’s history can be traced back to the early Indus Valley Civilization some 5,000 years ago, the word swastika itself comes from the Sanskrit ‘svastika’ meaning ‘good fortune’.

No one knows the true origins of this cross with its arms at right angles (sometimes with a dot in each of the four quadrants), but many historians believe it represents the movement of the sun across the sky.

The swastika was also used in many other cultures beside that which emerged in the Indus Valley. It appears frequently on coins from ancient Mesopotamia, and was known in pre-Christian European cultures where archaeologists have found the symbol on a number of artifacts.

Later in history, the swastika was called the ‘gammadion’ in Byzantine and early Christian art; in Scandinavia it was the symbol of Thor’s hammer.

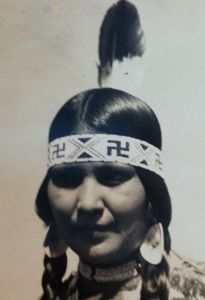

By the Middle Ages, although it was not frequently used, the swastika was well known throughout the world. In England it was called the ‘fylfot’, in Germany the ‘hakenkreuz’, the Greeks called it ‘tetraskelion’, the Chinese named it ‘wan’; it also appears in artifacts from the Mayan peoples in Central and South America, and was used by native American peoples, particularly the Navajo.

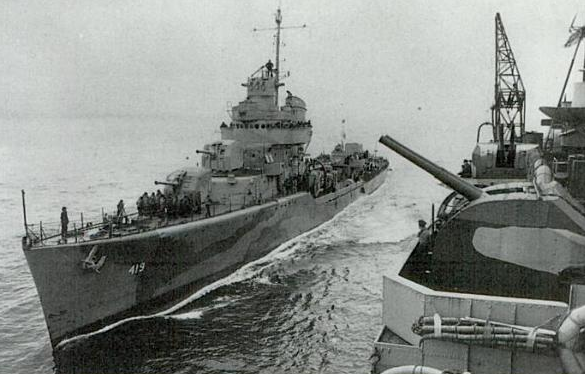

For 5,000 years the swastika symbolized power, the sun, life, good luck and strength; even as late as the early 20th century it was used throughout the world as a decoration on buildings, coins, and even cigarette cases; during its early days the Finnish Air Force used the symbol, and the US 45th Infantry Division wore a swastika on their shoulder patches during the First World War.

So, what happened to change of meaning of such an ancient and benign symbol?

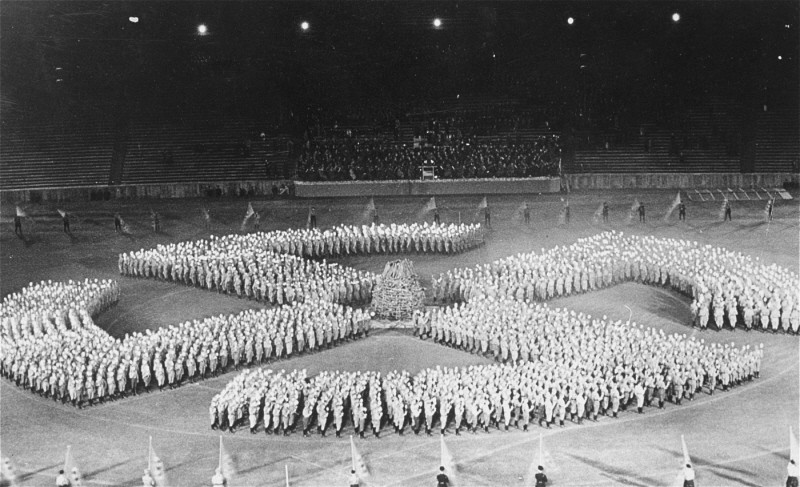

Europeans in the 19th century were fascinated by the ancient civilizations of India and the Near East. One of the great archaeologists of the time was Heinrich Schliemann, who spent years searching for the historical site of the city of Troy; when he found it he also found ancient carvings of the swastika. Historians were surprised to find the symbol was very similar to others which had been found on German pottery and began to speculate that there was once a vast Aryan culture which spanned Europe and Asia. It was not long, however, before nationalists began to claim that Aryanism was not about a common culture but that the Aryans were a superior race, and that Germans were their descendants. After German unification in 1841 German nationalists began to see themselves as the descendants of this ancient master race – the Aryans – and adopted the swastika as their symbol. By the early 20th century the majority of nationalistic societies in Germany were using it, so when Hitler decided that his fledgling Nazi Party needed a symbol of its own he adopted the swastika, and it became the official emblem of the party in the form we now know in 1920 – a red flag with a white circle, and the black swastika in its centre. Hitler described his new flag in his book ‘Mein Kampf’ as “In red we see the social idea of the movement, in white the nationalistic idea, in the swastika the mission of the struggle for the victory of the Aryan man, and, by the same token, the victory of the idea of creative work, which as such always has been and always will be anti-Semitic.” Hitler’s words were the first time that this ancient symbol of good luck was linked with anti-Semitism and death. In September 1935 Hitler went one step further and made the swastika the national flag of Germany. It was a powerful symbol utilizing the colours of Imperial Germany with an identification as ‘the master race’ intended to instill pride in the German people, and fear into Jews and other enemies of Nazi Germany.

At the same time that the swastika became Germany’s national flag the German government passed the Nuremberg Race Laws, including the Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honour, which further discriminated against Jews. Part of the reason for the enacting of these laws was the way in which the Nazi party, and the swastika, were being seen abroad. On 26th July 1935 the SS Bremen, a German passenger liner which was docked in New York, was the focus of a protest against increasing anti-Semitic incidents in Berlin, and the swastika was taken from the ship and thrown into the river. Although the police arrested a number of the demonstrators Germany issued a formal protest to the Americans, and when the courts freed the majority of the defendants Hitler passed the Reich Flag Law. In these laws, sexual relations and marriage were forbidden between Germans ‘or those of kindred blood’ and Jews, and Jews were banned from using the new national flag or even displaying the nation colours.

The use of the swastika as the national flag of Germany ended in May 1945 with the nation’s surrender at the end of the war. The Allied governments, who controlled the defeated nation, banned all Nazi organisations and their symbols – to use the swastika became a criminal act. Today the public display of Nazi symbols, including the swastika, is banned in Germany and many other European countries. It is not, however, against the law to display Nazi symbols and propaganda in the United States which has a strong tradition protecting the freedom of speech. In neo-Nazi groups throughout the world the swastika is still the most popular symbol.

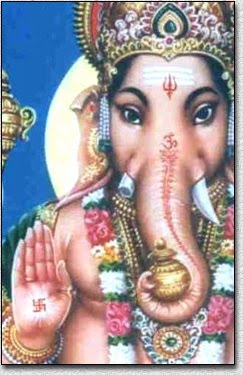

So, what does the swastika mean to people today? If you are Buddhist or Hindu you will still use it as a religious symbol of good luck, but the majority of the world is unaware of this and only see it as a symbol of hate. How can one differentiate between the two? Well, if you look closely you will see that the arms of the cross in the Nazi symbol radiate clockwise, whilst the symbol of eastern religions usually radiates anti-clockwise, although both are known in Hinduism – the left-hand/anti-clockwise is more technically known as the sauvastika and has always meant the opposite to the swastika – the right-handed standing for the good whilst the left-handed symbolises night, magical practices and Kali, the terrifying Hindu goddess; it is probably not surprising that Hitler chose the sauvastika version to represent the Nazi party.

The right-hand/clock-wise symbol is the one you will see whilst travelling in the Far East. It must be a great sadness to Hindus to hear people calling the swastika a symbol of hate when, for them, it is the most widely used auspicious symbol in their religion, as it also is for Jains and Buddhists. For Jains it is the emblem of their Seventh Saint, as well as the four arms of the swastika symbolizing the four possibilities for re-birth, depending on how you live this life – birth in the animal or plant world, on Earth, in hell, or in the world of spirits. For Buddhists, the swastika symbolizes the footprints or feet of the Buddha; it is often found at the beginning and end of religious inscriptions, and it was via Buddhism that the swastika found its way to Japan and China where it symbolizes long life and prosperity.

If you travel in India you will see the swastika, which is one of the 108 symbols of Vishnu, wherever you look – they are used on the opening pages of account books, during marriage services, on cars and lorries, on the walls of temples houses and other buildings, and even on clothing. In many pictures and statues gods and goddesses are shown with a swastika on the palm of the hand, and it is considered to be a very auspicious sign if a person has the shape of a swastika in the lines of their palm, the swastika might be worn as jewellery. It is even used as a girl’s name.

So, whenever you see a swastika take a moment to look closely at it and its context. Is it being used as a sign of hate? Or as an ancient symbol of good fortune?

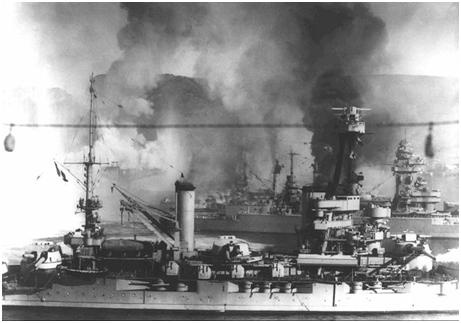

Norway had declared herself neutral at the outbreak of war in 1939, but the country’s strategic position meant that both Britain and Germany had an interest in what was happening there. In particular, the port of Narvik was important to the Germans as it allowed passage through the North Sea for the iron ore which the Nazis obtained from Sweden thus avoiding the Baltic Sea, parts of which regularly froze during the winter months. Almost as important for the Germans as this sea route, if not more so, was the fish oil which was produced in huge quantities in Norway. Why fish oil, you ask? Well, surprisingly, it was used to produce glycerin, which was then used to make nitroglycerin – a major component of dynamite.

Norway had declared herself neutral at the outbreak of war in 1939, but the country’s strategic position meant that both Britain and Germany had an interest in what was happening there. In particular, the port of Narvik was important to the Germans as it allowed passage through the North Sea for the iron ore which the Nazis obtained from Sweden thus avoiding the Baltic Sea, parts of which regularly froze during the winter months. Almost as important for the Germans as this sea route, if not more so, was the fish oil which was produced in huge quantities in Norway. Why fish oil, you ask? Well, surprisingly, it was used to produce glycerin, which was then used to make nitroglycerin – a major component of dynamite.

Lyudmila Belova was born 12th July 1916 in Bila Tserkva in the Ukraine (near Kiev). Her mother was a school teacher and her father a factory worker who worked his way up to a position of responsibility. Unfortunately, that meant that he had to move to a new town every year which in turn meant that Lyudmila had to start again each year at a new school with new friends.

Lyudmila Belova was born 12th July 1916 in Bila Tserkva in the Ukraine (near Kiev). Her mother was a school teacher and her father a factory worker who worked his way up to a position of responsibility. Unfortunately, that meant that he had to move to a new town every year which in turn meant that Lyudmila had to start again each year at a new school with new friends.

On her first day on the battlefield Lyudmila was frozen with fear and couldn’t bring herself to lift her gun and fire on the enemy. Then a young Russian soldier moved beside her but before he could settle in a shot rang out and he was killed. The shock spurred Lyudmila to action as she had liked the ‘nice, happy boy’, and from that moment on there was no stopping her.

On her first day on the battlefield Lyudmila was frozen with fear and couldn’t bring herself to lift her gun and fire on the enemy. Then a young Russian soldier moved beside her but before he could settle in a shot rang out and he was killed. The shock spurred Lyudmila to action as she had liked the ‘nice, happy boy’, and from that moment on there was no stopping her.

Lyudmila was shot four times whilst on active service and also suffered numerous shrapnel wounds although these did not stop her and she continued to fight. After being hit in the face by shrapnel from a mortar shell the ace sniper was withdrawn from the battlefield (by submarine from Sevastopol) to spend a month in hospital. Rather than sending her back to the front the Soviet High Command posted Lyudmila to train snipers, she was also given the role of propagandist.

Lyudmila was shot four times whilst on active service and also suffered numerous shrapnel wounds although these did not stop her and she continued to fight. After being hit in the face by shrapnel from a mortar shell the ace sniper was withdrawn from the battlefield (by submarine from Sevastopol) to spend a month in hospital. Rather than sending her back to the front the Soviet High Command posted Lyudmila to train snipers, she was also given the role of propagandist. Eleanor Roosevelt was very impressed with the young Russian and gave her advice on public speaking. As they travelled through 43 states Lyudmila’s confidence grew and she and the First Lady became very good friends. This boost in confidence became obvious when they reached Chicago and Lyudmila confronted the men in the audience by saying “Gentlemen, I am 25 years old and I have killed 309 fascist occupants by now. Don’t you think, gentlemen, that you have been hiding behind my back for too long?” She also addressed the subject of equality by saying “Now [in the U.S.] I am looked upon a little as a curiosity, a subject for newspaper headlines, for anecdotes. In the Soviet Union I am looked upon as a citizen, as a fighter, as a soldier for my country.”

Eleanor Roosevelt was very impressed with the young Russian and gave her advice on public speaking. As they travelled through 43 states Lyudmila’s confidence grew and she and the First Lady became very good friends. This boost in confidence became obvious when they reached Chicago and Lyudmila confronted the men in the audience by saying “Gentlemen, I am 25 years old and I have killed 309 fascist occupants by now. Don’t you think, gentlemen, that you have been hiding behind my back for too long?” She also addressed the subject of equality by saying “Now [in the U.S.] I am looked upon a little as a curiosity, a subject for newspaper headlines, for anecdotes. In the Soviet Union I am looked upon as a citizen, as a fighter, as a soldier for my country.”

Awards and honours

Awards and honours

Three days after the plane was shot down the New York Times reported that “It was believed in London that the Nazi raiders had attacked on the outside chance that Prime Minister Winston Churchill might be among the passengers.” When secret files about Ultra (the Allies’ secret Nazi code-breaking capabilities) were finally made public decades after the Second World War it was learned that the British had known in advance that the Germans assumed Churchill was on Flight 777 and so might target the plane. It was obviously vital for the war effort that Ultra could not be compromised and so the intelligence was not passed on to the Portuguese authorities or the airline. When Churchill wrote his history of the war he fed the flames of the mistaken-identity thesis when he referred to Leslie Howard’s death as one of “the inscrutable workings of fate.”

Three days after the plane was shot down the New York Times reported that “It was believed in London that the Nazi raiders had attacked on the outside chance that Prime Minister Winston Churchill might be among the passengers.” When secret files about Ultra (the Allies’ secret Nazi code-breaking capabilities) were finally made public decades after the Second World War it was learned that the British had known in advance that the Germans assumed Churchill was on Flight 777 and so might target the plane. It was obviously vital for the war effort that Ultra could not be compromised and so the intelligence was not passed on to the Portuguese authorities or the airline. When Churchill wrote his history of the war he fed the flames of the mistaken-identity thesis when he referred to Leslie Howard’s death as one of “the inscrutable workings of fate.”