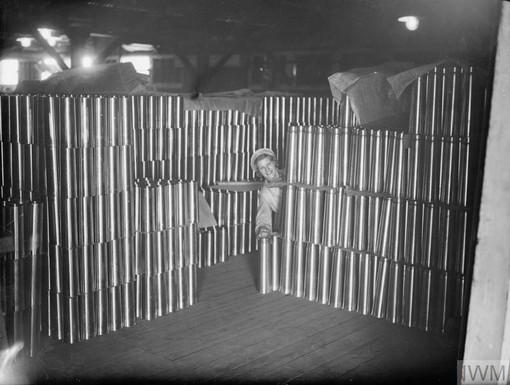

This year sees 75 years since the end of the Second World War and no doubt there will be many events to commemorate that fact. Often memorials focus on the soldiers who fought and died for their country, but while the men were away at the front it fell to the women to work in the factories and fields on the Home Front of England. Approximately 950,000 women worked in the munitions factories alone, producing the shells and bullets used by their fathers, husbands, and sons at the front. One of the largest of these factories was at Rotherwas, Herefordshire, which employed up to 4,000 women at its height and produced around 70,000 shells a week. Many of the women who worked there were as young as 16 but others were considerably older, some were even the daughters of women who had worked in the munitions factories during the First World War.

This year sees 75 years since the end of the Second World War and no doubt there will be many events to commemorate that fact. Often memorials focus on the soldiers who fought and died for their country, but while the men were away at the front it fell to the women to work in the factories and fields on the Home Front of England. Approximately 950,000 women worked in the munitions factories alone, producing the shells and bullets used by their fathers, husbands, and sons at the front. One of the largest of these factories was at Rotherwas, Herefordshire, which employed up to 4,000 women at its height and produced around 70,000 shells a week. Many of the women who worked there were as young as 16 but others were considerably older, some were even the daughters of women who had worked in the munitions factories during the First World War.

The job was relatively well-paid for a woman at that time, but the hours were long with the women often working eleven- or twelve-hour shifts to keep the factories running day and night. During these mammoth shifts the workers were only allowed a couple of short breaks, and this went on day after day, seven days a week, with just the occasional leave day granted every now and then. As well as long hours the job was also dangerous. There was the ever-present threat of an explosion, and the women suffered physically due to the effects of the chemicals which they were handling constantly. The TNT reacted with melanin in the body causing the women’s skin and hair to turn yellow, which earned them the nickname ‘Canary Girls’. The effects of the chemicals were more than skin deep however, as any of the women who became pregnant whilst working there gave birth to yellow ‘Canary Babies’. The colour gradually faded away but the women must have been afraid that there might be long term effects on their new born babies.

Little, if any, training was given to the women who worked in the munition’s factories – they would simply turn up for their first shift and within minutes were filling shells with TNT. It was delicate work as they collected the hot explosives from a huge mixer (something like a cement mixer), filled the shells and inserted the tube to take the detonator which they then had to tap in very carefully in order not to cause an explosion. In other parts of the factory women had to clean the shells ready to be filled, they did this by rubbing a pad on something like an emery board before inserting the pad into the top part of the shell, this was followed by another disc, tiny screwdrivers and screws were used to finish the fuse and put it in place. It was tedious, and dangerous, work. As well as the constant fear of explosions the workers were also at serious risk from accidents with dangerous machinery. It was not uncommon for women to lose fingers and hands, to suffer burns and blindness. In February 1944 19 workers, mainly women, were in a shed in the Royal Ordnance Factory in Kirby, Lancashire when one of the anti-tank mine fuses they were working with exploded, setting off a chain reaction amongst the other fuses. The girl who was working on that tray was killed outright, her body blown to pieces, other workers were injured, one fatally, and the factory badly damaged. There were also explosions at factories in Barnbow near Leeds, Chilwell in Nottinghamshire and Ashton-under-Lyne.

To reduce the risk of explosions the women had to pass through the `Shifting House` twice daily – on the way in to work and on the way out again. This was a long building divided down the centre by a red barrier, one side being the dirty side and the other side the clean. Such were the fears that a rogue spark caused by static might lead to an explosion that the women were banned from wearing nylon and silk. On arriving to start their shift their outdoor clothing, jewellery and hairpins were removed along with any matches and metallic items in their pockets (although jewellery was taken off women could continue to wear their wedding rings as long as they were taped up). The women would then be checked for any metallic fasters on their under garments (only lace up corsets could be worn, no bras with metal clasps) before they could pass to the clean side and put on their regulation cream coloured gowns buttoned right up to their neck and tight around their wrists, and their regulation issue hats – a tightly fitted mop cap with as much hair tucked away under it as possible. Of course, at the end of a shift or to leave the danger buildings area for any reason the complete reversal had to be undertaken so to save time the women were not allowed out on their breaks but had to use their own canteen inside the Danger Building where everything was stained the same ubiquitous yellow as the girls.

If the dangers inherent in the job weren’t enough there was always the threat of bombing by the Germans. The factory at Rotherwas was bombed at dawn on 27th July 1942 when the Luftwaffe dropped two 250kg bombs on the 300 acre site. The women were coming to the end of their shift and ran out when the sirens sounded. To their dismay they found that the air-raid shelters were locked so they sought cover wherever they could. The attacking plane flew in so low that the women could clearly see the black cross on its wings and the bombs falling from beneath it. There was a direct hit which ignited some of the munitions on the ground, the result was absolute carnage – from one unit of two hundred and thirty women only two survived.

It is a credit to the Canary Girls that despite all that they endured they rarely complained about the terrible working conditions, they were proud to know that they were doing their bit for the war effort and saw it as a patriotic duty. These women were putting their lives on the line every bit as much as the men who had gone to war, yet the numbers of women who were killed or seriously injured whilst working in the munitions factories is not known, and few people know of the work that they did and its lasting effects on their lives. Although the Canary Girls lost their yellow colouring when they left the factories the women often suffered with illnesses in later life ranging from throat problems to dermatitis, the most debilitating was a liver disease called toxic jaundice caused by prolonged exposure to TNT, which often proved fatal. As we celebrate 75 years since the end of the war this year, I hope we take time to remember all those who served, including the Canary Girls of the munition’s factories.

Chanel’s relationship with von Dincklage was no secret, and the Free France Secret Services seem to have known about the work that she was doing for him. When Paris was liberated on 25th August 1944 citizens sought out any collaborators, particularly women who had had relationships with the Germans. Just four days later, on 29th August 1944 two FFI resistance fighters arrested Chanel at the Ritz and she was questioned by the Free French Purge Committee about her work as a German agent. It has been implied that Churchill remembered their previous friendship and intervened with de Gaulle, for she was released after just two hours questioning, and in September 1944 Chanel re-joined von Dincklage in Switzerland. In 1949 Chanel once more faced questions about how she used the anti-semite laws to try to gain control of Parfums Chanel from the Wertheimer brothers, her relationship with von Dincklage, and her work for the Abwher, but denied all accusations against her. Chanel continued to live with von Dincklage until the mid 1950’s. She returned to Paris in 1954 and reopened her couture business with help from her friend Pierre Wertheimer, the man she had sought to destroy during the war but who was now reconciled to her (Amiot had returned the company to the Wertheimers at the end of the war). The fashion business of Coco Chanel prospered as never before.

Chanel’s relationship with von Dincklage was no secret, and the Free France Secret Services seem to have known about the work that she was doing for him. When Paris was liberated on 25th August 1944 citizens sought out any collaborators, particularly women who had had relationships with the Germans. Just four days later, on 29th August 1944 two FFI resistance fighters arrested Chanel at the Ritz and she was questioned by the Free French Purge Committee about her work as a German agent. It has been implied that Churchill remembered their previous friendship and intervened with de Gaulle, for she was released after just two hours questioning, and in September 1944 Chanel re-joined von Dincklage in Switzerland. In 1949 Chanel once more faced questions about how she used the anti-semite laws to try to gain control of Parfums Chanel from the Wertheimer brothers, her relationship with von Dincklage, and her work for the Abwher, but denied all accusations against her. Chanel continued to live with von Dincklage until the mid 1950’s. She returned to Paris in 1954 and reopened her couture business with help from her friend Pierre Wertheimer, the man she had sought to destroy during the war but who was now reconciled to her (Amiot had returned the company to the Wertheimers at the end of the war). The fashion business of Coco Chanel prospered as never before.

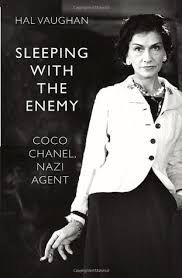

Another example comes from Hal Vaughan’s book ‘Sleeping with the Enemy: Coco Chanel’s Secret War’. He spent a lot of time reviewing American, German, French, and British archives, and says that Abwehr Agent 7124 whose code name was ‘Westminster’ went on missions around Europe to recruit new agents for the Third Reich, travelling to Spain with Baron Louis de Vaufreland, a Frenchman who worked as an agent for the Germans; his job was to find people who could be recruited or coerced to spy for Germany, and as Chanel knew the British ambassador to Spain she went with him as cover, and to offer him introductions.

Another example comes from Hal Vaughan’s book ‘Sleeping with the Enemy: Coco Chanel’s Secret War’. He spent a lot of time reviewing American, German, French, and British archives, and says that Abwehr Agent 7124 whose code name was ‘Westminster’ went on missions around Europe to recruit new agents for the Third Reich, travelling to Spain with Baron Louis de Vaufreland, a Frenchman who worked as an agent for the Germans; his job was to find people who could be recruited or coerced to spy for Germany, and as Chanel knew the British ambassador to Spain she went with him as cover, and to offer him introductions.

Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler, a Jew born in Vienna on 9th November 1914, is better known to the world as the Hollywood actress Hedy Lamar. As a child she was interested in acting and theatre, but she also had a passion for inventing things and at the age of 5 she was able to take apart and rebuild her old-fashioned music box. Her father was a banker who loved Hedy’s intellectual curiosity and interest in technology and would happily spend time explaining to her how things worked. Hedy grew up to be one of the most beautiful women in the world and began her acting career in Europe where at the age 16 she went to a film studio and got a walk on part. The young actress became world famous when she appeared naked in a film called Ecstacy which was banned by Hitler and denounced by the Pope. When she was 19 Hedy married a munitions tycoon, Fritz Mandl, who was allied with the Nazis even though he was Jewish; it was not a happy marriage. By 1937 it was clear that war would be inevitable; Jews were being systematically denied their rights which led to the death of Hedy’s father from stress and worry. Hedy left her husband and escaped to England with her mother where Hedy met the film director Louis B Mayer and went to Hollywood to work for him.

Hedwig Eva Maria Kiesler, a Jew born in Vienna on 9th November 1914, is better known to the world as the Hollywood actress Hedy Lamar. As a child she was interested in acting and theatre, but she also had a passion for inventing things and at the age of 5 she was able to take apart and rebuild her old-fashioned music box. Her father was a banker who loved Hedy’s intellectual curiosity and interest in technology and would happily spend time explaining to her how things worked. Hedy grew up to be one of the most beautiful women in the world and began her acting career in Europe where at the age 16 she went to a film studio and got a walk on part. The young actress became world famous when she appeared naked in a film called Ecstacy which was banned by Hitler and denounced by the Pope. When she was 19 Hedy married a munitions tycoon, Fritz Mandl, who was allied with the Nazis even though he was Jewish; it was not a happy marriage. By 1937 it was clear that war would be inevitable; Jews were being systematically denied their rights which led to the death of Hedy’s father from stress and worry. Hedy left her husband and escaped to England with her mother where Hedy met the film director Louis B Mayer and went to Hollywood to work for him.

This is where her friend the composer George Anthiel came in. George came up with the idea which would make Hedy’s concept work using the same system as that used by pianos which play themselves – the rolls activate piano keys so why couldn’t they activate radio frequencies in both the torpedo and the ship? The idea was for two rolls of card with holes in them (similar to those used by the pianos) to start at the same time and run at the same speed so the ship and torpedo could secretly communicate on the same pattern of frequencies; there were 88 frequencies, the number of keys on a piano, and it would be impossible for the enemy to jam these all at the same time as it would require too much power; it would also be almost impossible to crack the system as each pair of rolls could be uniquely created using a random pattern. George and Hedy took their idea to the National Inventors Council in 1941, and the Council put them in touch with a physicist at Cal Tech called Sam Mackeown, who was an expert on electronics. On 11th August 1942, U.S. Patent 2,292,387 was granted to Antheil and “Hedy Kiesler Markey”, Lamarr’s married name at the time. George and Hedy took the invention to the navy but they rejected it, and the US government seized her patent in 1942 as the ‘property of an enemy alien’.

This is where her friend the composer George Anthiel came in. George came up with the idea which would make Hedy’s concept work using the same system as that used by pianos which play themselves – the rolls activate piano keys so why couldn’t they activate radio frequencies in both the torpedo and the ship? The idea was for two rolls of card with holes in them (similar to those used by the pianos) to start at the same time and run at the same speed so the ship and torpedo could secretly communicate on the same pattern of frequencies; there were 88 frequencies, the number of keys on a piano, and it would be impossible for the enemy to jam these all at the same time as it would require too much power; it would also be almost impossible to crack the system as each pair of rolls could be uniquely created using a random pattern. George and Hedy took their idea to the National Inventors Council in 1941, and the Council put them in touch with a physicist at Cal Tech called Sam Mackeown, who was an expert on electronics. On 11th August 1942, U.S. Patent 2,292,387 was granted to Antheil and “Hedy Kiesler Markey”, Lamarr’s married name at the time. George and Hedy took the invention to the navy but they rejected it, and the US government seized her patent in 1942 as the ‘property of an enemy alien’.

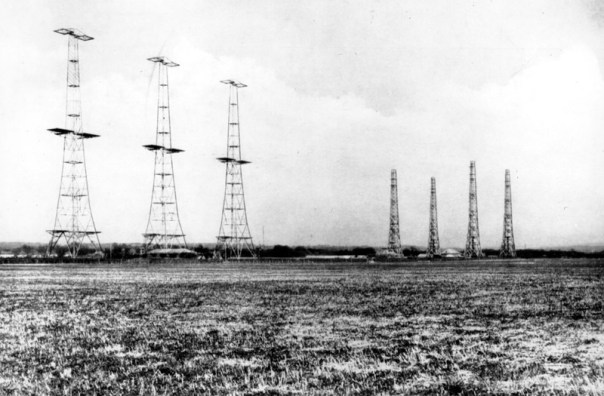

Women in the WAAF worked in these radar centres. When a signal was received from approaching aircraft it was displayed on a green cathode ray tube. This showed the pulse sent out by the transmitter moving in from the edge of the screen with the target aircraft positioned in the centre. The screen could be calibrated for anything up to 200 miles which enabled the operator to ‘zoom in’ on the approaching craft. The radar operator would move a cursor over the position of the aircraft and the information was automatically sent to a calculating machine along with further information which enabled it to work out the plane’s height as well as position. This information was then sent to the mapping room with a large table on which the planes were positioned, a visual aid which made it easier for non-technical officers to direct the defending planes.

Women in the WAAF worked in these radar centres. When a signal was received from approaching aircraft it was displayed on a green cathode ray tube. This showed the pulse sent out by the transmitter moving in from the edge of the screen with the target aircraft positioned in the centre. The screen could be calibrated for anything up to 200 miles which enabled the operator to ‘zoom in’ on the approaching craft. The radar operator would move a cursor over the position of the aircraft and the information was automatically sent to a calculating machine along with further information which enabled it to work out the plane’s height as well as position. This information was then sent to the mapping room with a large table on which the planes were positioned, a visual aid which made it easier for non-technical officers to direct the defending planes.