Leslie Howard was a superstar actor of his day. The son of Jewish immigrants from Hungary he was born in London in 1893 and served during the First World War, he was mustered out of the army a few weeks before the Battle of the Somme began in 1916 as he was suffering from shell shock. It was actually his doctor who suggested acting as a therapy little knowing that Howard would go on to international fame, particularly for his roles in Pygmalion and Gone With The Wind. When the Second World War broke out the English actor gave up his lucrative Hollywood contract (including his share of the box-office takings for Gone With The Wind) and returned home to see what he could do to further the war effort.

Howard was not the only Hollywood actor to join up at the first opportunity, Americans Kirk Douglas, Paul Newman and Charles Bronson also served whilst Clark Gable and James Stewart were awarded medals for their bravery; on the other side of the Atlantic British actors Richard Todd, Alec Guinness and Dirk Bogarde all served in the armed forces.

Leslie Howard, however, decided that rather than fighting he would put his acting skills to use and so offered to do whatever he could for the British government. One of the first things he was asked to do was to make broadcasts to the United States which still remained a neutral country with Churchill doing everything he could to get the Americans to join the war as Britain’s allies. Many women in America were isolationists and strongly against the war, it was recognised that their views had a not insubstantial effect on the views of American men so it was thought that a matinee idol such as Howard might go a long way towards making them change their minds. But America was only a part of his focus as Leslie Howard also made programmes for the domestic audience appearing on ‘Britain Speaks’ and making National Savings documentaries for the Ministry of Information. Many of his broadcasts focused on British values which the soldiers at the front were fighting to protect – freedom, tolerance and decency. The propaganda programmes which Howard was involved in were so successful that William Joyce (better known as Lord Haw Haw) singled out Howard as a target in his radio broadcasts from Europe (‘Germany Calling’) saying that he should ‘stick to acting’.

Howard’s work for the government also included directing, co-producing and starring in several war films including 49th Parallel, The First Of The Few (the story of RJ Mitchell, the inventor of the Spitfire) and Pimpernel Smith (based on the story of the Scarlet Pimpernel who rescued aristocrats from Paris during the French Revolution, only this time the plot revolved around an English professor rescuing refugees from the Germans). The work that Howard did was obviously propaganda but he felt that it was justified whilst the country was at war with Hitler, in one broadcast Howard even used what was considered strong language for the 1940’s when he said “To hell with whether what I say is propaganda or not, I’ve never stopped to figure it out and I don’t think it matters anymore.”

Howard had met Winston Churchill in 1937 when they had several informal talks where Howard made his anti-Nazi views known. Churchill remembered this and when he became Prime Minister he used Howard and other actors, including Laurence Olivier and Noel Coward, to get access to famous or important people who might be able to help with the war effort. To this end Howard went to Spain and Portugal in May 1943 purportedly to open links between Spanish and British film-makers and present a series of lectures on his films and the role of Hamlet, but it is believed that his real purpose was to try to prevent General Franco from joining the Axis powers. The Iberian peninsula was neutral during the war and so became a magnet for spies from both sides which meant that the actor was closely watched by German agents during his visit.

Howard left Portugal in June 1943 on a civilian Douglas DC-3 which flew regularly across the Bay of Biscay as there was an informal agreement for both sides to respect the neutrality of civilian planes. On this day, however, the agreement was ignored and six Junkers JU88 fighters shot it down killing all seventeen passengers and crew. The news of the death of incredibly popular Leslie Howard shocked the British people, and the reason for the German action raised many questions which have not been fully answered to this day.

Why was the plane shot down? Was it an accident or deliberate? If deliberate, who was the target?

One thing we do know is that this same plane making its daily Lisbon to London run had been attacked for the first time two weeks earlier, but it was assumed that the aircraft had been hit by mistake and so the flights continued. Now the plane had been fired on again, and this time shot down with a number of people on board who could have been a possible target. There was Arthur Chenhall, Howard’s manager who was travelling with him and who looked a lot like Churchill. There was also Kenneth Stonehouse who was a reporter for Reuters, Wilfred Israel who was a Jew from Berlin whose work with the Kindertransport had been, in part, the inspiration for Pimpernel Smith, Tyrrel Shervington who was the Lisbon manager for the Shell Oil Company, and Ivan Sharp who had been negotiating tungsten and wolfram imports which were important for the British war effort and deals which the Germans would obviously like to prevent. Any one of these men could have been targeted by the Germans although many thought that the clear target was Howard as when Goebbels (the German Propaganda Minister) had seen the film Pimpernel Smith he had taken it as a personal parody of himself and wanted to kill the director and star.

There is, however, another possibility. On the same day that Howard’s ill-fated plane set off from Portugal Winston Churchill also took off from Gibraltar to return to Britain after a visit to North Africa. The British Prime Minister was to have flown in a similar flying boat and on a similar flight path to the plane which was shot down but, due to bad weather, he decided to take a bomber instead. The German pilots who brought down the plane took photographs of the wreckage before flying back to their base in France. So, was Leslie Howard the target of the German Junkers, or did they mistake the civilian plane for the one carrying the British Prime Minister? What a coup it would have been if they had been able to shoot down and kill the man who was the inspiration for so many of the Allies.

Three days after the plane was shot down the New York Times reported that “It was believed in London that the Nazi raiders had attacked on the outside chance that Prime Minister Winston Churchill might be among the passengers.” When secret files about Ultra (the Allies’ secret Nazi code-breaking capabilities) were finally made public decades after the Second World War it was learned that the British had known in advance that the Germans assumed Churchill was on Flight 777 and so might target the plane. It was obviously vital for the war effort that Ultra could not be compromised and so the intelligence was not passed on to the Portuguese authorities or the airline. When Churchill wrote his history of the war he fed the flames of the mistaken-identity thesis when he referred to Leslie Howard’s death as one of “the inscrutable workings of fate.”

Three days after the plane was shot down the New York Times reported that “It was believed in London that the Nazi raiders had attacked on the outside chance that Prime Minister Winston Churchill might be among the passengers.” When secret files about Ultra (the Allies’ secret Nazi code-breaking capabilities) were finally made public decades after the Second World War it was learned that the British had known in advance that the Germans assumed Churchill was on Flight 777 and so might target the plane. It was obviously vital for the war effort that Ultra could not be compromised and so the intelligence was not passed on to the Portuguese authorities or the airline. When Churchill wrote his history of the war he fed the flames of the mistaken-identity thesis when he referred to Leslie Howard’s death as one of “the inscrutable workings of fate.”

We will never know for certain the true circumstances of the death of Leslie Howard, but JB Priestley spoke for many when he made a broadcast after the actor’s death was announced on the BBC – “The war has claimed another casualty, the stage and screen have lost an unselfish artist, and millions of us have lost a friend.”

Despised for his weakness and regarded by his family as little more than a stammering fool, the nobleman Claudius quietly survives the intrigues, bloody purges and mounting cruelty of the imperial Roman dynasties. In I, Claudius he watches from the sidelines to record the reigns of its emperors: from the wise Augustus and his villainous wife Livia to the sadistic Tiberius and the insane excesses of Caligula. Written in the form of Claudius’ autobiography, this is the first part of Robert Graves’s brilliant account of the madness and debauchery of ancient Rome, and stands as one of the most celebrated, gripping historical novels ever written.

Despised for his weakness and regarded by his family as little more than a stammering fool, the nobleman Claudius quietly survives the intrigues, bloody purges and mounting cruelty of the imperial Roman dynasties. In I, Claudius he watches from the sidelines to record the reigns of its emperors: from the wise Augustus and his villainous wife Livia to the sadistic Tiberius and the insane excesses of Caligula. Written in the form of Claudius’ autobiography, this is the first part of Robert Graves’s brilliant account of the madness and debauchery of ancient Rome, and stands as one of the most celebrated, gripping historical novels ever written.

On 21 June 1922, Count Alexander Rostov – recipient of the Order of Saint Andrew, member of the Jockey Club, Master of the Hunt – is escorted out of the Kremlin, across Red Square and through the elegant revolving doors of the Hotel Metropol.

On 21 June 1922, Count Alexander Rostov – recipient of the Order of Saint Andrew, member of the Jockey Club, Master of the Hunt – is escorted out of the Kremlin, across Red Square and through the elegant revolving doors of the Hotel Metropol.

A stunning debut historical thriller set in the turbulent 14th Century for fans of CJ Sansom, The Name of the Rose and An Instance of the Fingerpost.

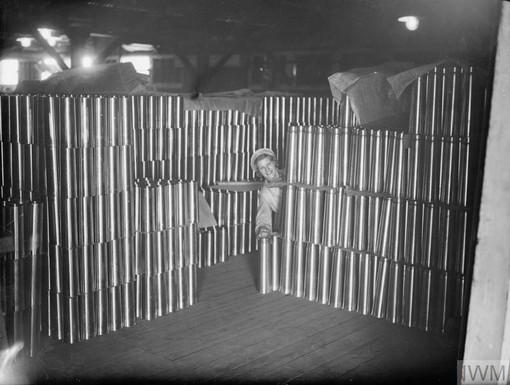

A stunning debut historical thriller set in the turbulent 14th Century for fans of CJ Sansom, The Name of the Rose and An Instance of the Fingerpost.  This year sees 75 years since the end of the Second World War and no doubt there will be many events to commemorate that fact. Often memorials focus on the soldiers who fought and died for their country, but while the men were away at the front it fell to the women to work in the factories and fields on the Home Front of England. Approximately 950,000 women worked in the munitions factories alone, producing the shells and bullets used by their fathers, husbands, and sons at the front. One of the largest of these factories was at Rotherwas, Herefordshire, which employed up to 4,000 women at its height and produced around 70,000 shells a week. Many of the women who worked there were as young as 16 but others were considerably older, some were even the daughters of women who had worked in the munitions factories during the First World War.

This year sees 75 years since the end of the Second World War and no doubt there will be many events to commemorate that fact. Often memorials focus on the soldiers who fought and died for their country, but while the men were away at the front it fell to the women to work in the factories and fields on the Home Front of England. Approximately 950,000 women worked in the munitions factories alone, producing the shells and bullets used by their fathers, husbands, and sons at the front. One of the largest of these factories was at Rotherwas, Herefordshire, which employed up to 4,000 women at its height and produced around 70,000 shells a week. Many of the women who worked there were as young as 16 but others were considerably older, some were even the daughters of women who had worked in the munitions factories during the First World War.