Today we have satellites travelling in orbit around the earth which can take incredibly detailed photographs of what is happening on the ground below, an invaluable aid to intelligence agencies everywhere. Surprisingly, Britain also had its own sophisticated ‘spy in the sky’ during the Second World War. Blue painted Spitfires armed with cameras instead of guns took tens of millions of aerial photos over enemy territory, ten million of which survive today and are stored in archives in Edinburgh.

The centre for this reconnaissance was RAF Medmenham based at Danesfield House 60 miles west of London, a Base rivalling the code-breaking Bletchley Park in its secrecy; and it was here that one of the most important stories of the war unfolded. With the clever use of a simple stereoscope the workers at Medmenham were able to scrutinise the spy photographs and bring every building and fold in the land to life in 3D. This enabled them to measure the height and width of objects and so gave a more accurate picture of their targets. Operatives at the Base assessed railways, factories, shipyards, and buildings; and they were always on the lookout for something ‘unidentified’, searching for anything unusual which might have a bearing on the course of the war.

The Photo Interpreters (PI’s) at Danesfield House were tasked with providing up to date and incredibly accurate information about the movements of the German war machine – during the war 80% of Britain’s intelligence came from photo reconnaissance and interpretation. The most important example of the work done at RAF Medmenham was Operation Crossbow which identified and hunted down something which had never been seem before – Hitler’s mysterious ‘V-weapons’, the new pilotless drones and rockets which could potentially have led to Germany finally winning the war.

Air reconnaissance really ‘took off’ in 1940 when the RAF created a special wing – the Photographic Reconnaissance Unit, and the secret of its success was its adapted Spitfires. These planes were painted a pale blue to be camouflaged against the sky at 30,000 feet, which was the perfect height for taking the photographs. The guns on the reconnaissance Spitfires were replaced by cameras but pilots didn’t worry about this as they had a cruising speed of 365 miles an hour and knew that no German plane would be able to catch them for most of the war, not until the Germans produced their jets in 1944 were the Spitfires in any real danger of pursuit. The planes from RAF Medmenham, flown by both British and American pilots, were able to cover great distances which allowed them to reach Berlin, they even photographed the entire Ruhr in a single mission. These pilots were incredibly skilled in flying alone, navigating to their target where they had to fly a straight and level course to prevent distortion of the photographs which were taken of targets out of sight directly beneath them. To achieve this they would roll the plane on their initial pass above the target to identify the key features, and then come in for a second pass when they took the pictures. Each plane had five very large cameras which were able to identify and photograph something as small as a man on a bicycle from 30,000 feet. To ensure the best quality images the cameras had to be heated at altitude whilst the pilots in their cockpits were left to endure the freezing cold for 5 hours at a time. Once the planes arrived back at base the PI’s took over.

The analysis of the aerial spy photos was three-phased. Stage 1 – as soon as the plane landed the films were developed and the negatives viewed. If something needed acting on immediately (say within about 24 hours) for example shelling or bombing a bridge where German troops were crossing, these would be given priority. Stage 2 – the photos were then developed; it seems almost impossible to believe, but 36 million prints were made during the war. The priority pictures were dealt with and the rest sent to Medmenham where the PI’s identified any targets which would need to be dealt with during the next week. Stage 3 – items which were more long term, factories or dams for example, were dealt with last.

Scrutinising and interpreting the photographs was not an easy task and PI’s were often recruited from professions where people were used to working precisely and in detail – many mathematicians, geologists and archaeologists were recruited from Oxford and Cambridge universities. As well as these skills a PI needed to think laterally and creatively and so staff were recruited from Hollywood with their artists eye for detail, some actors were also employed at Danesfield House, including Dirk Bogart. Around 150 women worked with the men as PI’s, helping to both identify targets and assess the damage inflicted in bombing raids to see if they had been successful or if the RAF needed to go back again.

Other countries had their own ‘spy planes’, but what made Medmenham unique was the way that they processed the information by taking ordinary 2D photos which had been shot in an overlapping sequence and looking at them through a stereoscope to create a 3D image. The pictures overlapped each other by 60% to give a very detailed image which the PI’s became experts at interpreting. It was this expertise which identified something strange in May 1942. A reconnaissance Spitfire pilot had seen something unusual at Peenemunde on the Baltic coast where he photographed a new airfield which had three large concrete and earth circles beside it. A great deal of attention was paid to the photographs, but no one could identify what the circles were, and after concluding that they might possible have something to do with sewage the pictures were shelved.

The story of Medmenham and Peenemunde might have ended there if it had not been for a curious incident in March 1943 when two German generals who had been captured in North Africa were bugged talking at Trent Park Military Prison. They were discussing a new secret weapon, a rocket which would soon be targeting England and would probably change the course of the war. On 23rd June 1943 the RAF spy planes were sent out to scour Germany and northern France to see if they could find any evidence of these weapons. Hundreds of photos were analysed by the PI’s who were told to look for tubes which could fire missiles at Britain from France – a daunting job when no one at that time had any idea what a missile site might look like. One keen-eyed PI spotted a tube on its side in one of the strange circles at Peenemunde, and with this knowledge they went back over previous photos and found a picture of one of the rockets in an upright position; thanks to their 3D technology they were able to work out the height of the object from its shadow – an impressive 14m.

Churchill’s chief scientific advisor Lord Cherwell refused to believe that Hitler had the technology to build such weapons so Medmenham needed to get more detailed information than could be seen from their simple 3D stereoscopes, what the needed was a Wild photogrammetric survey machine used for land surveys to get the detail needed to convince Cherwell. The problem was that the Wild machines were only available from Switzerland (a neutral country). Squadron Leader Ramsey Matthews arranged for a Swedish intermediary to buy two Wild A6 machines which were then shipped through Germany to Sweden before being flown to England. It was now possible to use the machines to analyse photos and get a greater understanding of Peenemunde, measuring the rockets and test sites with incredible accuracy so that scale models could be built, models which were convincing enough to persuade Cherwell that Hitler did indeed have a secret weapon.

Spy planes were sent out again and brought back more alarming photos from St Pol in northern France where they had found huge concrete bunkers and had no idea what they were for. Photos from 30,000ft didn’t help so pilots were sent in at just 30m high to get detailed close-up images; PI’s correctly identified these massive concrete structures as rocket launch sites. If Hitler was to be thwarted something needed to be done, and fast.

On 17th and 18th August 1943 more than 500 bombers set off from Britain to destroy Peenemunde. The raid did very severe damage putting back the missile programme by 8-12 weeks, but more importantly some of Germany’s most important rocket scientists were killed in the raid. The missile sites in northern France were then bombed as well even though the huge thick concrete domes were effectively bomb proof. The only bomb that could touch them was the 12,000lb Tall Boy and the even bigger Grand Slam bombs designed by Barnes Wallis. The bombs created a mini-earthquake which caused the huge domes to shift on their foundations (although not destroy them) effectively putting the sites out of action.

After the air-raids Hitler moved his V-weapons programme deep into Germany and Poland so that it could not be hit by the Allies again, so Medmenham turned its focus to finding launch sites in northern France – the ramps for the VI’s hidden in woodland were difficult to spot but, with perseverance, 96 sites were eventually identified by the PI’s, and on 1st December 1943 a V1 rocket was identified on a ramp for the first time. This was one more piece to the puzzle and the Photo Interpreters looked back at the 96 sites in northern France and were able to correctly identify them as V1 storerooms and launch sites aimed at Southampton, Portsmouth, and London. More importantly, VI’s fired from these sites would also be able to reach the proposed beachheads for the Allied invasion of Europe, for D Day to be successful the launch-sites would have to be wiped out before any invasion force set out – Operation Crossbow was planned to bomb the V1 sites, beginning on 23rd December 1943.

From early 1944 Medmenham was given a second focus – to help invasion planning by monitoring German activity in northern Europe, and every platoon commander on D Day had maps of minefields and defences in the area he was attacking, all supplied by RAF Medmenham. When the first V1’s began to land on London just days after D Day in June 1944 the PI’s again put all of their energies into looking for the launch-sites which had been moved from the woodlands and were now even more cleverly concealed in factories and amongst buildings. As the Allied invasion forces advanced they overran the V1 emplacements, and the last doodlebug fell on London 7th September 1944. One day later the first V2 travelled from mainland Europe at supersonic speed, coming out of nowhere with no warning to crash into Chiswick in London with devastating consequences. There was no defence against the new threat as V2 launch sites were mobile and so difficult to spot in time. Thankfully the Allied forces had already advanced to a point where the launch sites were soon pushed back out of range of England.

In a few short months Hitler’s V-weapons killed about 9,000 people in England, who knows how many more would have died and how much longer the war would have gone on if not for the work of the air reconnaissance at RAF Medmenham. And Operation Crossbow.

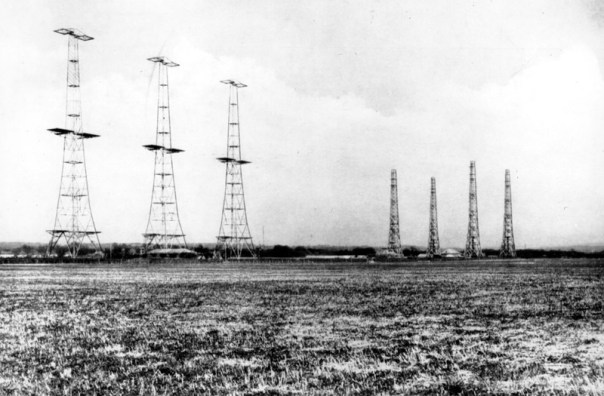

Women in the WAAF worked in these radar centres. When a signal was received from approaching aircraft it was displayed on a green cathode ray tube. This showed the pulse sent out by the transmitter moving in from the edge of the screen with the target aircraft positioned in the centre. The screen could be calibrated for anything up to 200 miles which enabled the operator to ‘zoom in’ on the approaching craft. The radar operator would move a cursor over the position of the aircraft and the information was automatically sent to a calculating machine along with further information which enabled it to work out the plane’s height as well as position. This information was then sent to the mapping room with a large table on which the planes were positioned, a visual aid which made it easier for non-technical officers to direct the defending planes.

Women in the WAAF worked in these radar centres. When a signal was received from approaching aircraft it was displayed on a green cathode ray tube. This showed the pulse sent out by the transmitter moving in from the edge of the screen with the target aircraft positioned in the centre. The screen could be calibrated for anything up to 200 miles which enabled the operator to ‘zoom in’ on the approaching craft. The radar operator would move a cursor over the position of the aircraft and the information was automatically sent to a calculating machine along with further information which enabled it to work out the plane’s height as well as position. This information was then sent to the mapping room with a large table on which the planes were positioned, a visual aid which made it easier for non-technical officers to direct the defending planes.

We have all seen photos of Winston Churchill giving his famous ‘V for Victory’ sign during the Second World War, but we actually have Belgian tennis star Victor de Laveleye to thank for this iconic sign. de Laveleye competed in the 1920 and 1924 Olympic Games for Belgium, but he was also a politician who served as Minister of Justice in 1937. As the Germans pushed west in 1940 de Laveleye fled to Britain where he was put in charge of the BBC’s broadcasts to occupied Belgium and soon became the symbol of free Belgians everywhere. On 14th January 1941 Laveleye asked all Belgians to use the letter ‘V’ as a symbol of resistance and a rallying cry to fight the invaders because, he said, ‘V is the first letter of Victoire (victory) in French and Vrijheid (freedom) in Flemish, like the Walloons and the Flemish who today walk hand in hand, two things that are consequences of each other, Victory will give you Freedom’. He went on to say that “the occupier, by seeing this sign, always the same, infinitely repeated, [will] understand that he is surrounded, encircled by an immense crowd of citizens eagerly awaiting his first moment of weakness, watching for his first failure.” The Belgian people willingly adopted the sign and the letter immediately began to appear daubed on walls in Belgium, the Netherlands, Northern France, and other parts of Europe, a symbolic act of defiance against the Nazis.

We have all seen photos of Winston Churchill giving his famous ‘V for Victory’ sign during the Second World War, but we actually have Belgian tennis star Victor de Laveleye to thank for this iconic sign. de Laveleye competed in the 1920 and 1924 Olympic Games for Belgium, but he was also a politician who served as Minister of Justice in 1937. As the Germans pushed west in 1940 de Laveleye fled to Britain where he was put in charge of the BBC’s broadcasts to occupied Belgium and soon became the symbol of free Belgians everywhere. On 14th January 1941 Laveleye asked all Belgians to use the letter ‘V’ as a symbol of resistance and a rallying cry to fight the invaders because, he said, ‘V is the first letter of Victoire (victory) in French and Vrijheid (freedom) in Flemish, like the Walloons and the Flemish who today walk hand in hand, two things that are consequences of each other, Victory will give you Freedom’. He went on to say that “the occupier, by seeing this sign, always the same, infinitely repeated, [will] understand that he is surrounded, encircled by an immense crowd of citizens eagerly awaiting his first moment of weakness, watching for his first failure.” The Belgian people willingly adopted the sign and the letter immediately began to appear daubed on walls in Belgium, the Netherlands, Northern France, and other parts of Europe, a symbolic act of defiance against the Nazis.

Winston Churchill realised how successful this symbol was in uniting people against Hitler’s regime and decided to use it during a speech in July 1941 when he said that ‘The V sign is the symbol of the unconquerable will of the occupied territories and a portent of the fate awaiting Nazi tyranny. So long as the people continue to refuse all collaboration with the invader it is sure that his cause will perish and that Europe will be liberated.” Churchill continued to use the sign as his ‘signature gesture’ for the remainder of the war.

Winston Churchill realised how successful this symbol was in uniting people against Hitler’s regime and decided to use it during a speech in July 1941 when he said that ‘The V sign is the symbol of the unconquerable will of the occupied territories and a portent of the fate awaiting Nazi tyranny. So long as the people continue to refuse all collaboration with the invader it is sure that his cause will perish and that Europe will be liberated.” Churchill continued to use the sign as his ‘signature gesture’ for the remainder of the war.

As we commemorate the ending of the First World War it is fitting that we remember all those who paid the ultimate price. We are all aware of cemeteries around the world which contain the graves of soldiers who died far from home, and if you have ever visited one you will have been impressed by the standard of care which is taken to keep these places of remembrance at their best. This work is carried out by The Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) which was the brainchild of Sir Fabian Ware. The CWGC builds and maintains cemeteries and memorials in more than 150 countries and territories and also creates and preserves archives with extensive records of the fallen. Ware was 45 when war broke out and so too old to fight but he was determined to play his part so became the commander of a mobile unit in the British Red Cross. Arriving in France in 1914 he was appalled and saddened at the huge loss of life he saw, and also by the fact that there was no official way of documenting and recording the graves. Determined that none of the fallen would be forgotten he organised for his unit to begin recording and caring for all the graves they could find. Municipal cemeteries were soon full and Ware negotiated for France to grant land in perpetuity to Britain which would become responsible for the management and maintenance of the graves there. People heard about Ware’s work and he began to get letters from people asking for photographs of the graves of their loved ones. By 1917 17,000 photos had been sent. At the same time graves were being recorded in Egypt, Greece and Mesopotamia as well as France.

As we commemorate the ending of the First World War it is fitting that we remember all those who paid the ultimate price. We are all aware of cemeteries around the world which contain the graves of soldiers who died far from home, and if you have ever visited one you will have been impressed by the standard of care which is taken to keep these places of remembrance at their best. This work is carried out by The Commonwealth War Graves Commission (CWGC) which was the brainchild of Sir Fabian Ware. The CWGC builds and maintains cemeteries and memorials in more than 150 countries and territories and also creates and preserves archives with extensive records of the fallen. Ware was 45 when war broke out and so too old to fight but he was determined to play his part so became the commander of a mobile unit in the British Red Cross. Arriving in France in 1914 he was appalled and saddened at the huge loss of life he saw, and also by the fact that there was no official way of documenting and recording the graves. Determined that none of the fallen would be forgotten he organised for his unit to begin recording and caring for all the graves they could find. Municipal cemeteries were soon full and Ware negotiated for France to grant land in perpetuity to Britain which would become responsible for the management and maintenance of the graves there. People heard about Ware’s work and he began to get letters from people asking for photographs of the graves of their loved ones. By 1917 17,000 photos had been sent. At the same time graves were being recorded in Egypt, Greece and Mesopotamia as well as France.